Jigsaw puzzle maths

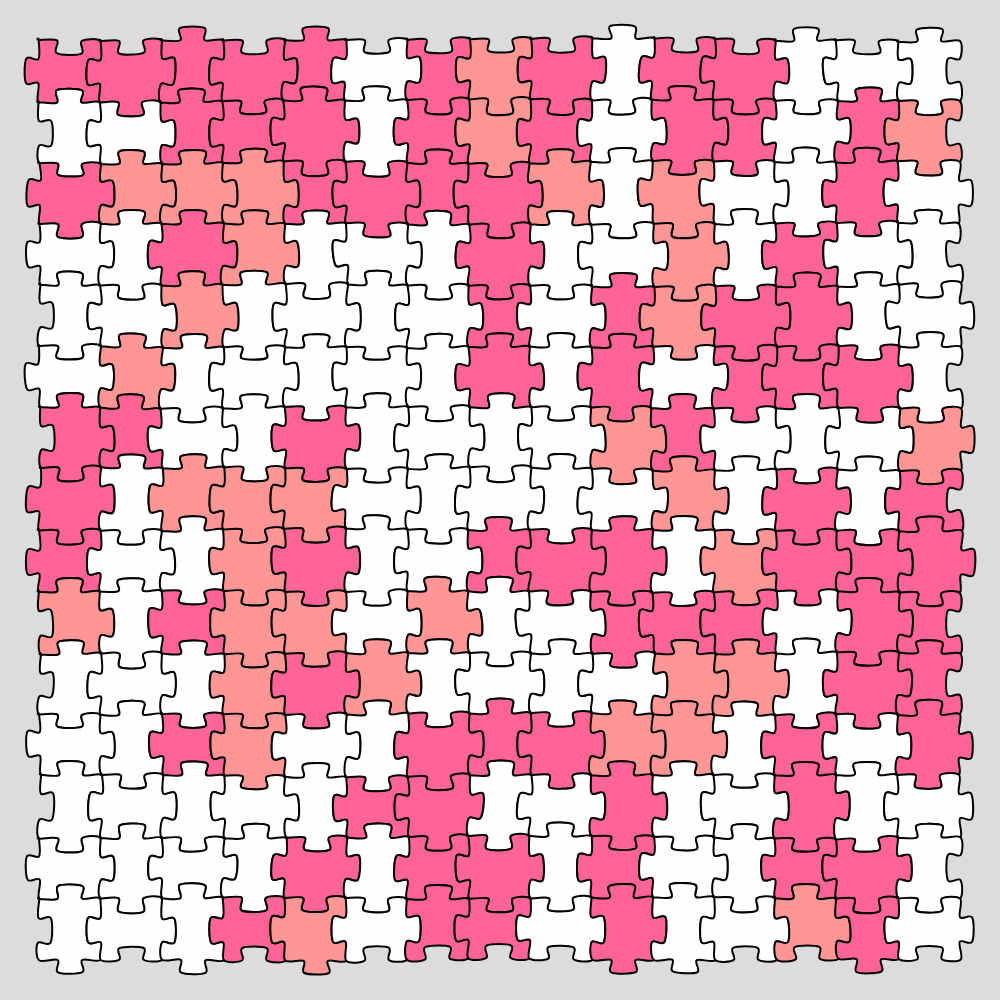

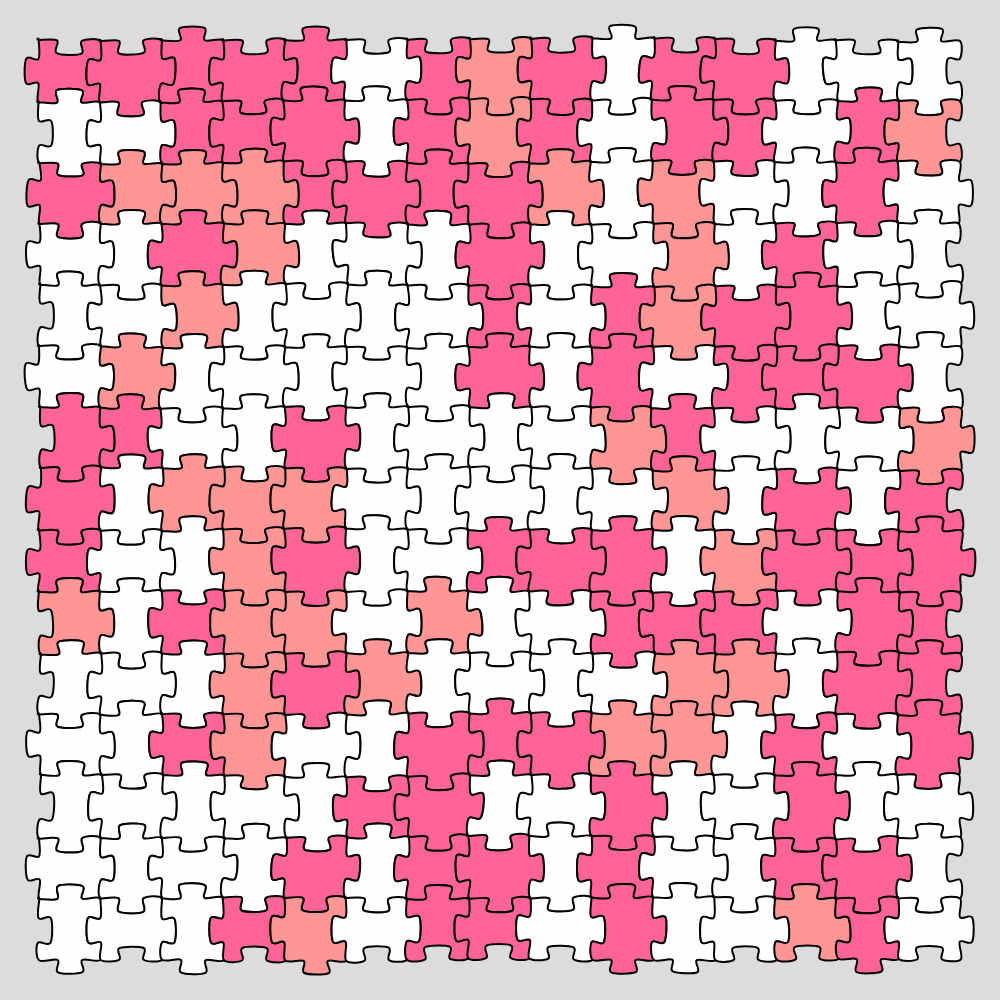

If I were to ask you to imagine a jigsaw puzzle, you will probably think of something like this, at least as far as puzzle shapes are concerned:

And if I were to ask you to think of a single jigsaw puzzle piece, chances are good that you would be thinking about the "regular" puzzle pieces that have two out-jutted tabs opposite each other (and two blanks, also on opposite sides). Like this piece:

Is this the most common piece?

However, there is nothing inherent in jigsaw puzzles that should make this the most common piece!

Assume that every side of a jigsaw puzzle piece has a 50% chance of being a tab, and a 50% chance of being a blank. Then, the probability of getting a "regular" puzzle piece can be calculated as:

If you were to count the pieces in the image at the top of the article, you would find that 111 of 225 pieces are "regular", or about 44%. That's way more than the 12.5% we just calculated!

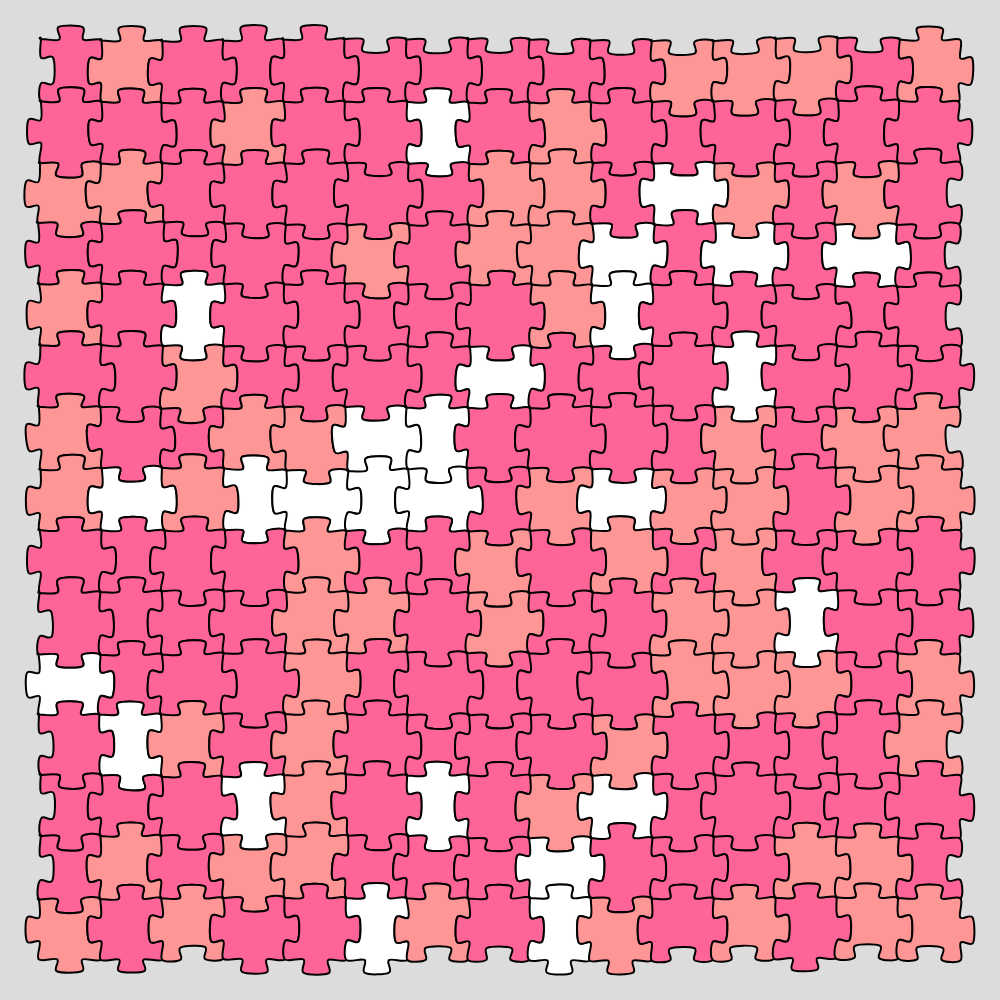

Investigating further, here is what a puzzle with fully-randomized tabs/blanks would look like:

There are far more "regular" pieces in your typical puzzle than in this random sample.

...We have to conclude that jigsaw puzzle makers have been secretly colluding and tweaking probabilities to ensure that "regular" pieces are more common than they should be! It is all a conspiracy of big regular jigsaw piece!!

Where permutations are stifled, exploits proliferate

But, as it's usually the case when you tweak the probabilities of a random process to make an uncommon output more common, you inadvertently make it easier to guess what the output would be.

And, thanks to our advanced (read: highschool 😇) level of math knowledge, we can use this to our advantage when solving jigsaw puzzles!

Anisotropic checkerboards

If most pieces of a puzzle are "regular" pieces, it stands to reason that large areas of the puzzle are covered by alternating horizontal and vertical pieces. Like a checkerboard!

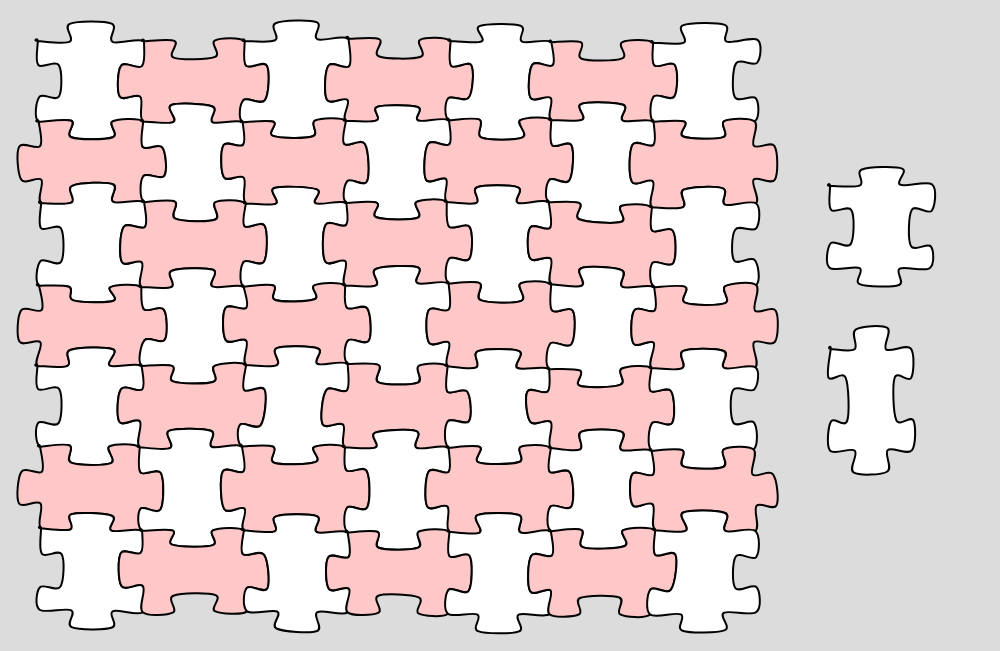

If the pieces are not perfectly square, we can already use this to our advantage by separating the "vertical" and "horizontal" pieces into separate groups. Then, for every position we need to fill, we would know which pile we should be looking through.

For example, in the image below, with short, wide pieces, you can easily tell that one of the two pieces set aside is a "horizontal" piece because it is longer in the same direction that the tab jut out in (same as the other horizontal pieces, here colored in pink), and that the other piece is a "vertical" piece, because it is shorter in the direction of its tabs: and that's despite me rotating the two pieces to have the same orientation.

If you were trying to find where you can place a piece, you can already eliminate half the available positions just by using this trick!

Pip-counting

However, there is an even better trick available when you consider the connections between pieces.

Most of the time, a piece will connect to a "regular" piece—just because there are so many "regular" pieces out there!

But what about the irregular ones?

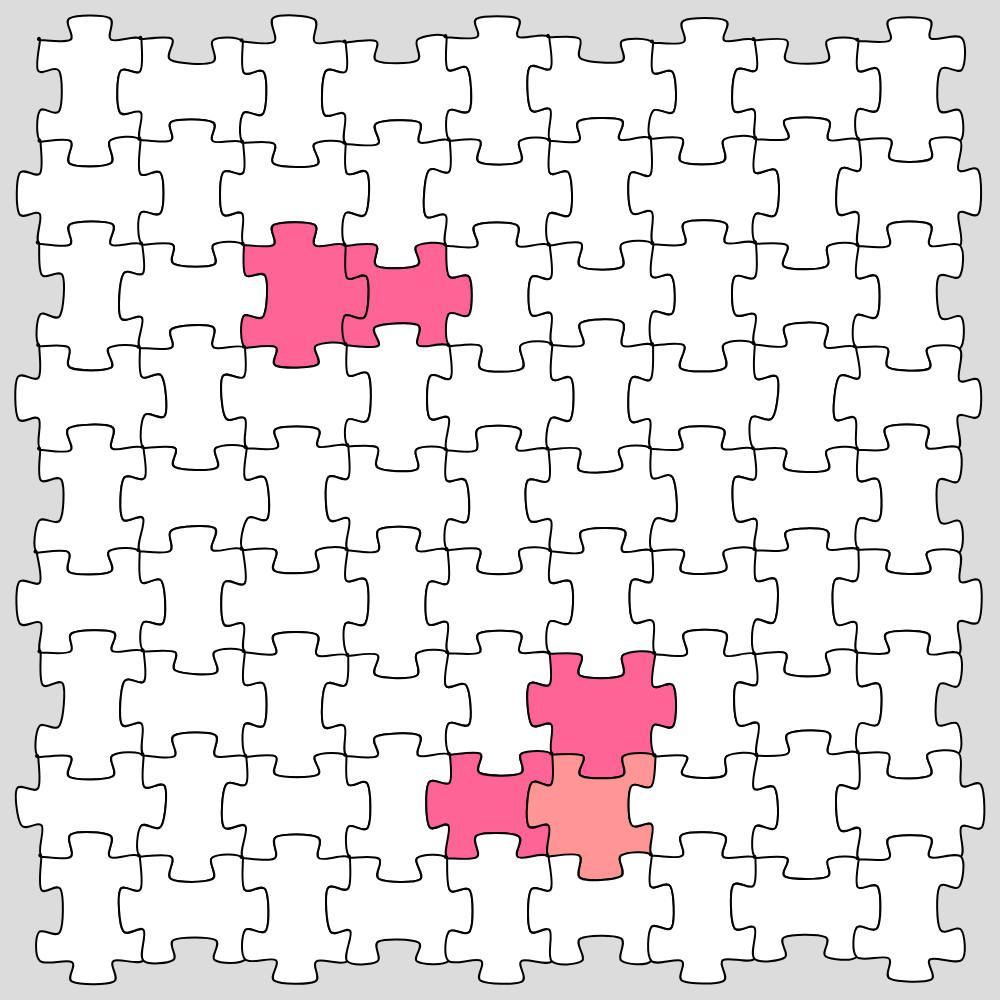

You are not likely to find a piece with 3 tabs connected to regular pieces on all four sides. That's because it interrupts the checkerboard pattern... and also because, when most pieces have 2 tabs and 2 blanks, a piece with 3 tabs and 1 blank needs to be matched with a piece of more blanks than tabs elsewhere.

Instead, what you are likely to find is a "source" piece with 3 tabs connecting straight to a "sink" piece with 3 blanks, in the sea of regular pieces. The two connect in such a way that they don't interrupt the checkerboard pattern; and the pair of such "3-pieces" and "1-pieces" is very common.

Furthermore, when a piece with 3 tabs does not neighbor a piece with 3 blanks, you are very likely to find an intermediate "bend" piece with 2 tabs around the same corner and 2 blanks opposite of those tabs... which then connects to both the piece with 3 tabs, and the piece with 3 blanks. That is to say, the "bend" pieces (colored in light pink in the image), form "paths" between the "source" pieces with 3 or 4 tabs to the "sink" pieces with 3 or 4 blanks (both colored in darker pink).

So, if you find an irregular piece in a puzzle, you can try to see if any other irregular piece is right next to it.

And if you were to sort all the irregular pieces aside, you can even assemble patches of them, possibly faster than if you tried assembling patches by colors or pattern.

Conclusion

So, there you have it: two simple math-inspired tricks you can use when solving a jigsaw puzzle!

You probably already knew them, but in case you didn't: now you do.

If you want to play with the program I wrote to generate the images in this article, you can do so on in the "Fun" section of this website. 😁

Or, if you just want an image of the "checkerboard" pattern of regular pieces and the "paths" or "patches" of irregular pieces, here is the image from the start again:

This was my 38th article for #100DaysToOffload.

Browse more articles?

|← Articles tagged math (1/1) →|

← Shoestring lentils Articles tagged 100DaysToOffload (38/38) →|

← Shoestring lentils Articles on this blog (45/45) →|